High-impact ruling that went mostly under the radar of technological companies, and relevant media outlets at the time. Returning now, in 2022, to that ruling as it's starting to materialize in other court rulings.

Use of Google Analytics violates "Schrems II" decision by CJEU.

The conclusion to one complaint, out of 101, filed by the noyb (None Of Your Business) organization, as a direct follow-up of the Schrems II ruling.

The Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) have been anything but fast-moving. Such complaints are highly reliant on citizen — or NGO — initiatives, thus they generally target big companies or egregious violations. Having said that, I think it might be a good moment to take a look at how exactly we got where we are today, and what impact on the technology sector these rulings might have.

I am not a lawyer, and this article does not constitute legal advice. It's merely an attempt to open the topic to a larger audience without getting lost in acronyms and abbreviations.

General Data Protection Regulation, at a glance

The GDPR set a legal baseline on how EU residents' personal data

can be processed,

stored, accessed, and audited. Defines who the custodians, and users of this data, are.

Further referred to as data controllers

and data processors

.

Additionally, citizens are granted the right to decide how their personal data

is: collected, rectified,

processed, deleted, and exported.

Within the GDPR personal data

encompasses any information that can

be used independently, or collectively, to identify or profile individuals.

An important aspect of this definition, is that a single data point — public

by design, mind you — would need the same types of guarantees around its protection as any other

type of personal data

. This public data point, the so-called IP address, proves problematic

in practice, and is an issue we'll be returning to later.

What's an IP address?

An Internet Protocol (IP) address is a virtual address assigned to each Internet-connected device. Much like real-world addresses, these identifiers are necessary for the recipients at each end of an Internet connection to know where to deliver the data. This type of address is assigned on-demand to the device by the Internet Service Provider (ISP) the moment the device connects to the Internet. Because of the way the assignment is done, the same device won't have the same address when used at home, in the office, in a coffee shop. It can also differ at various times of the day when the device is used from the same location.

A data controller

is the entity that decides what user data it needs and wants to collect.

Under the GDPR any organizational entity that interacts electronically with an EU resident is

already a data controller

by default (email, name, phone numbers; it's all personal data

).

Two major constraints about what data controllers

collect, or is collected

on their behalf:

- The amount of

personal data

collected should be minimized (so-called principle ofdata minimization

). Emphasis to collect only what's necessary in order to provide services to the user. - Any collection of non-essential

personal data

, or usage ofpersonal data

for other purposes than those agreed upon, mandate user explicit consent.

Example of essential personal data

collection

An eCommerce website can be entitled to request personal datalike address, name, phone number for a user that is about to place an order for a physical product. However, if the website sells digital products they might be entitled to request the users' email address, but not their phone number. And if they would like to send future promotional emails, they would need to explicitly have users' consent for their data to be used in marketing.

At the other of the GDPR we have data processors

, those who use the personal data

collected by (or on behalf of) the data controllers

to process it for the purposes agreed upon between

the users and the data controllers

. In the modern interconnected and highly externalized

service world, a data controller

typically operates with multiple data processors

.

The data processors

need to also comply with the agreements made between the data controllers

and the users.

To simplify compliance when exporting data to US services, EU entities tried to shield themselves behind the so-called Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs). A set of European Commission “pre-approved” template contracts that stipulated appropriate data protection safeguards for both parties of the agreement. The SCCs preceded the GDPR by a couple of years and would prove later on as insufficient to ensure compliance.

Awareness, compliance, and fines in practice

Even though the GDPR was adopted in 2016, discussion in the technology sector was mostly non-existent until a few months away from the 25th of May 2018 enforcement date. The general population was more or less broadly informed about GDPR, through the large amounts of emails sent out by companies on the week leading up to that date.

Large organizations had the legal departments to be compliant to a higher degree. Small and medium organizations, were left to their own devices, needing to rely on either external consultants (of legal and technical expertise) or supporting vendors to work out compliance on their behalf. This is visible as both an end-user of digital products and as a consultant working on projects. There seems to be a tacit supposition that enforcement is absent in practice, except for Big Tech. Not wrong, when looking back at historical data, however…

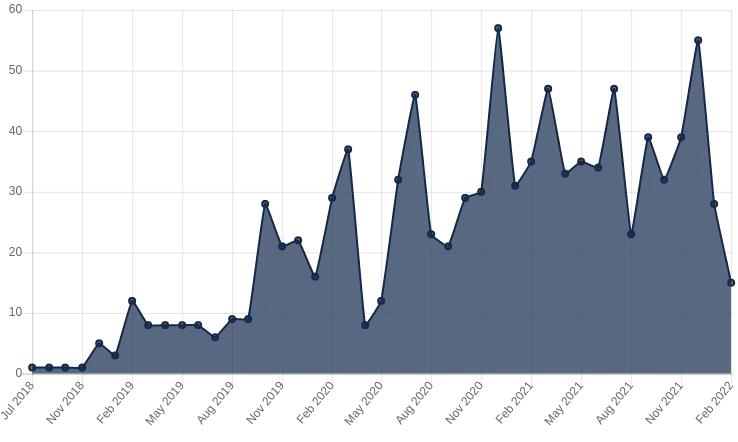

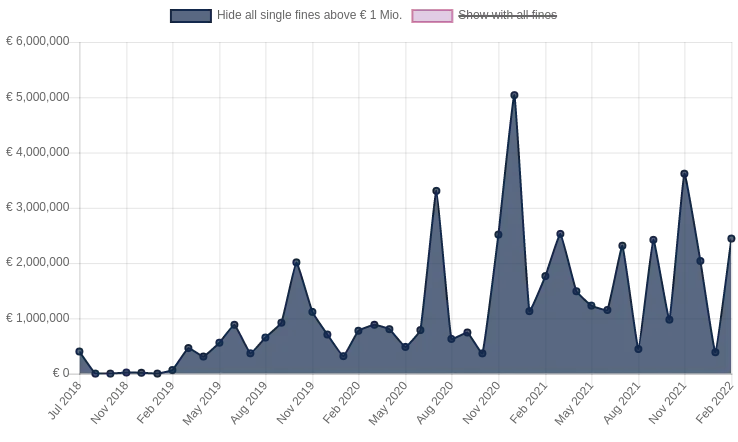

Organizations should be aware that enforcement processes are improving. It might be just that newly created enforcement entities (Data Protection Authorities) had learning curves to overcome, with regard to: compliance assessment, the collaboration between EU member states, and escalation of judicial processes. This is the theory I use to justify the slow upwards trend in fines issued; illustrated by the following graphs:

The sum of fines graph presented above, excludes the large individual fines that would make the other data points too small to compare. Of those fines, a brief sample of fines issued last year to internationally recognized entities:

| Data Controller | Fine € | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Amazon Europe Core S.à.r.l. | 746 million | 16th of July, 2021 |

| WhatsApp Ireland Ltd. | 225 million | 2nd of December, 2021 |

| Google LLC | 90 million | 31st of December, 2021 |

| Facebook Ireland Ltd. | 60 million | 31st of December, 2021 |

| Google Ireland Ltd. | 60 million | 31st of December, 2021 |

Constantly at odds:

privacy and national security priorities

The Schrems II ruling made SCCs an unfit legal instrument for the stricter privacy compliance rules that the GDPR

requires. Furthermore, the 2021 updated SCCs were careful to

strictly define what privacy risks should be accounted for by data importers

. There are multiple clauses

about personal data

access by law enforcement agencies. One example:

Annex document, Clause 14. a.

The Parties warrant that they have no reason to believe that the laws and practices in the third country of destination applicable to the processing of the personal data by the data importer, including any requirements to disclose personal data or measures authorising access by public authorities, prevent the data importer from fulfilling its obligations under these Clauses.

Even if no personal data

is exported to a third-party country,

the mere collaboration with such a third-party country could still make the company non-compliant.

This is exemplified best by the January 2022

Austrian DPA decision

which stated that usage

of Google Analytics is a violation of GDPR data transfer requirements. One argument raised is

that even if Google Analytics does not store any identifiable information right now, it could still be forced by

law enforcement agencies to do so in the future.

An interesting, and valid, argument to present, but also a textbook definition of double standards. Within

the EU personal data

can move freely because all member states are adopters of the GDPR, but also because

localized adoption of any EU regulation loses precedence to national security laws. The same laxness

is not available for non-EEA countries. For more details, you can read

How Europe’s Intelligence Services Aim to Avoid the EU’s Highest Court—and What It Means for

the United States.

I've seen voices praising these decisions. As a privacy advocate myself, welcome better safeguards around

personal data

protection. However, asking entities to be compliant with nation-states in mind, is just

asking the impossible. Even within the strong privacy advocating communities,

it's understood that extreme privacy precautions and practices become void in the presence of a

motivated and well-funded state actor.

Privacy conflicting legislation is what causes the existing landscape. And there needs to be governmental initiative to get us out of this conflict. Otherwise, the end result can be nothing more than a further siloed internet where US and the EU service providers are disjointed, and overall it'll result in less choice for end-users.

A possible future regulatory approach

23rd of March 2018, former president of the US, Donald Trump signed into law the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (CLOUD Act). It extended the power of US law enforcement agencies, by allowing them to request US based entities to share user data even if it's stored abroad. Abolishing this act, would once again, make usage of US services privacy compliant when EU resident data is stored in the EU.

The EU–US Privacy Shield was a framework for regulating transatlantic exchanges of personal data for commercial purposes between the European Union and the United States. Creating an improved EU-US Privacy Shield that nullifies parts of the CLOUD Act when EU resident data is at play, would help. It would be wise to involve Max Schrems (and privacy advocacy groups) when drafting this new EU-US treaty. Given that the Schrems II ruling invalidated the existing EU-US Privacy Shield, and the Schrems I ruling invalidated the International Safe Harbor Privacy Principles treaty that preceded it.

Due to the way that personal data

is defined within the GDPR, I've mentioned that IP addresses are problematic

in practice. Having a piece of identifiable information — public by design — visible by all parties

involved in a internet connection, immensely complicates compliance. We need this type of information to be anonymized

at the source, and the only way that is possible is by shifting the privacy responsibility of this information

from user-facing services to Internet Service Providers (ISPs). And no, there's no switch that ISPs can toggle

and be done, it would require research, development and investment. But the cost of having all internet enabled

services take care individually of this information, as opposed to a few thousand EU ISPs, is not even comparable.

Things to keep in mind going forward

EU digital services.

Decisions from EU authorities and escalating fines will

likely push companies to seek out EU alternatives to existing US services. I'm seeing shifts

to alternative analytics and cloud providers already.

The EU alternatives market is small by any comparable criteria. Websites like european-alternatives.eu exist, nowhere near comprehensive in their listings. It's the perfect time for EU companies to develop competing services to already established US players. And where such services exist, to invest in ecosystem and marketing.

In-house data processing.

SMEs will want to reduce their third-party data processor

footprint by either hosting their own services, or dropping external providers for custom internal functionality.

While a common practice already in the large enterprise sector, for security, and costs reasons. In the SMEs

sector, this move would have the opposite effect in the short term. Would increase overall operational costs,

and weaken the security of personal data

, due to lack of staffing and operational knowledge by your everyday SME.

This would possibly increase demand in technical and legal knowledge, that could create an environment where SMEs would get out-priced even more when hiring workers. At the same time, it would provide a fertile environment for startups that develop on-premise, managed, non Software as a Service (SaaS) business products.

Compliance & enforcement.

The numbers shared previously on fines are not impressive, given how large internet services sector is. Precisely

why the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) has called for a conference on the

16-17 of June 2022. The premise of this conference seems to imply that

a more centralized EU privacy enforcement process would expedite things.

The Future of Data Protection: effective enforcement in the digital world

From the leaflet: “the conference will seek to explore both constructive improvements

that exist within the current framework, but also alternative models of

enforcement of the GDPR, including a more centralised approach.”.

Regardless of the approach taken, the expectancy is that pace at which complaints are resolved, as warnings or fines, is going to increase significantly. I already think we are on that path, but the outcome of the conference will be just as important to keep an eye out for, even if any decision would take years to implement.

GDPR compliance is not straightforward in practice, and different entities comply to different degrees. The fact that complaints need to be raised by individuals — or NGOs — made entities less prompt in fixing their technical, legal and organizational issues. Right now we are at a point where enforcement is starting to pick up pace, especially when talking about large entities. And by the looks of it, 2022 might be the year when SMEs are caught in the crossfire and issued regulatory fines just the same.

In the short term, the services market will see shifts to EU providers and more centralized processing of data in order to simplify compliance. In the long run, regulatory changes might be necessary to ease the technical pressure on large companies, but more importantly, on the SME sector.